Prototyping

Prototypes are very useful. We use them all the time when developing new products. They let us try out new ideas explore how well a particular technology will work for a specific application.

One danger of a prototype, is that there is the temptation to think that you can then just fix it up to make it into a product. This is a common enough dilemma with software. It mostly works so a bit more polish and it will be OK to ship it. This is definitely a danger zone. Once a prototype has served it’s purpose, put it aside. Then design the product from the ground up. And then, if you can use any of the prototype design, then do so in a considered way based on the design and architecture you have determined will meet the entire needs of the project. Most prototypes do not have the exception handling and support featured needed to make them into real products that can be tested and maintained.

So I was interested to read about another potential problem with prototypes in the December 2011 edition of the Harvard Business Review in an article titled Early Prototypes Can Hurt A Team’s Creativity.

Innovation Blockage

The problem outlined is that the prototype can limit the thinking about the project. It is way easier to pick and choose features on a defined thing and critique flaws than to create something new. So the early prototype can really set the team back if they let it define the full scope of how to think about the underlying problem being solved.

I have seen the same think happen when a product needs a new model. It is obvious to look at incremental improvements and “Low Hanging Fruit” but sometimes you have to step back and think about the market and the customers and what they really need. Maybe it is time for a clean slate. And maybe there are good reasons why the old technology the product was based on is not the right choice for the next model.

In both cases, the prototype and the existing model act as a frame of reference that limits innovation and creativity.

The hard part of course, is recognising when that is the case and when it is not.

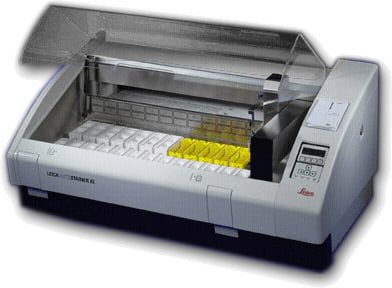

As an example, one project I worked on early in my career involved creating a new international product for a company entering a new market. It was for an existing category and there were 6 incumbents who had been there for a while, in some cases 30 years. The company did something very wise. They sent someone to talk to several opinion leaders and to all the local users of the equipment. The intent was to determine the best way to go about gaining market share. The story told was that none of the existing products met the customer needs really well. Over time they had converged into 2 formats, one for each market segment, and it was a price war as the products had become commodities. But when they were asked what they were trying to do, the customers gave two clear stories, one in each market segment. The marketing and product specifications were based on these two stories and we designed a single product to meet both market segments. The product entered a crowded international market at a price point 50% above the next most expensive product. The company planned to sell 300 in the first year and ramp up after that. They sold 1500 in the first year and had to move to a larger factory to satisfy the demand.

I also got a patent for one of the new technologies developed. The point is that if you meet the actual need, people will pay for that. The issue in this market was that the incumbents had let each others’ offerings define their responses and not the customers’ need. Another example of stifled innovation until a new player listened and changed the game.

I have never forgotten that lesson.

Successful Endeavours specialise in Electronics Design and Embedded Software Development. Ray Keefe has developed market leading electronics products in Australia for nearly 30 years. This post is Copyright © 2012 Successful Endeavours Pty Ltd